Consistency is Not the Goal

July 07, 2024

Way back in one of my first software internships, I remember overhearing a conversation from another engineer. I don’t remember much of the details, honestly, except that this one engineer was pretty frustrated with another about some recent code that was checked in. His last line was “Let’s be consistent.” as he walked back to his own cubicle, clearly agitated.

As I mentioned, I don’t know all the details of what apparently needed to be consistent, but it stuck with me (clearly). I carried it through my first few professional years as an engineer. I wanted to write consistent, clear, crisp code. It felt like an unspoken rule that great codebases were consistent with no exceptions.

As I’ve grown in my career, I’ve realized that while consistency is a good goal in software development, it isn’t the goal.

Consistency Isn’t the Goal

Before going on, let’s first emphasize consistency is good. Being consistent in creating and practicing daily habits that lead to health, knowledge, etc. are great tools for our growth. Being consistent in treating others with respect and kindness is essential, too.

But in our software development, it’s not nearly as important. There are benefits, of course, in some areas of our systems. Things like:

- Consistent auth across services

- Consistent style guides across public interfaces and APIs (including things like event definitions)

- Consistent (enough) logging

- Consistent languages across your tech stack

You could take it further for things like naming or other styles, but most value is found across public interfaces or message structures. Internal libraries that expose public APIs should also try to use consistent structures and styles.

Beyond that, I’ve found that pushing for too much consistency can harm a codebase.

What happens is that an engineer might write a function or snippet of code to solve a problem. They get it working and commit it to main.

Another engineer sees it and, without really understanding it, adopts it into their own code. Another engineer follows and notices the “pattern” of this code being used. They, in turn, follow suit. Then another and another.

Instead of having a codebase in which engineers have spent time applying critical thinking to their problems, they’ve adopted pattern hunting.

Pattern Hunting

I’ve written about patterns previously, and have tilted my hand that while patterns are useful we tend to overuse them in many contexts.

One of the core reasons why we overuse them is we’ve stopped using them to solve problems we encounter. Instead, we go looking for places to implement a pattern we’ve learned about or seen elsewhere. While it might sound similar, it’s dramatically different.

In the former, you have a problem to solve and research the right solutions or patterns to use to help solve it. In the later, you have a shiny new pattern (or new technology) that you want to use no matter what. In this case, you’ll use a complex pattern to abstract what could have been a simple if statement or function variable.

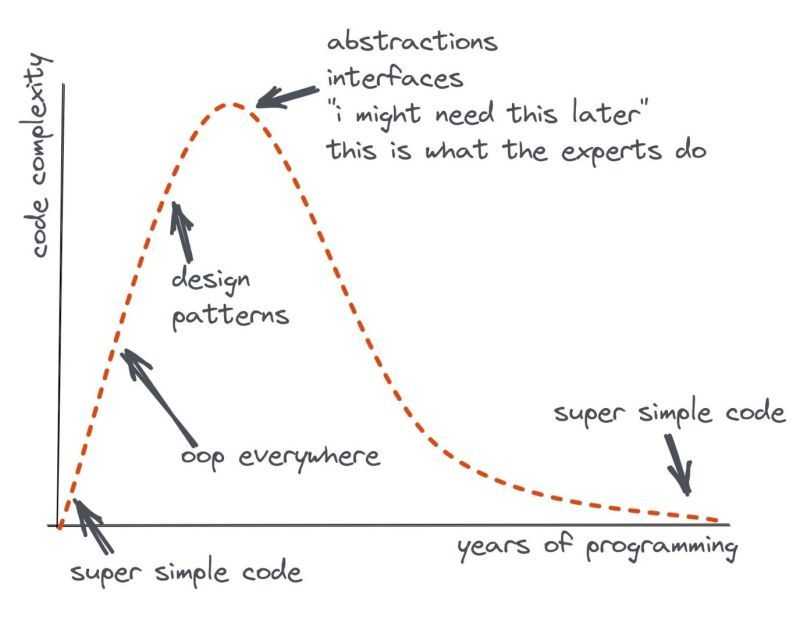

The graph below shows a common (and somewhat caricatured) view of how engineers often progress through their coding patterns in their careers.

Credit to Rob Kerr’s post with this chart.

Many engineers will quickly point out that abstractions and interfaces are critical to writing good software. And they are right!

The difference is between engineers who understand when and why to use those tools and those who try to “do what experts do.” The latter—“consistency for consistency’s sake”—leads to one thing: a mess.

Too Much Consistency Hampers Innovation

Beyond pattern hunting, consistency can also stifle innovation and keeps the code from evolving overtime.

Take for example an application struggling to keep up with load. An engineer notices that almost all of the application uses a connection factory that creates a new connection on every database query (!). This engineer decides to use a connection pool from an OSS library to see if it would help.

As data-driven engineers, they decided to measure their experiments, and—tada!—the connection pool works! However, the queries in this part of the application required some rework.

This engineer is also reasonably cautious and doesn’t want to rework the entire application’s code immediately to use the connection pool. Instead of refactoring all the code at once, they push their change for only a few pieces of the application first to make sure it does work in production before doing a large overhaul. Once they get the data, they start working through the rest of the application to use the pool.

In this example, there are two times the engineer might have gotten pushback on consistency.

The first is the problem itself. Should they have ignored it since changing the application (one of several others the team owns) across the team would create inconsistency? It would seem shortsighted to avoid taking measures and carefully improving performance when needed simply to keep things consistent.

The second is the deployment strategy. Should this engineer have “cowboy coded” their refactor and pushed the entire application to prod in one deploy? It would be risky, especially for something the team is still learning to use, measure, and understand.

If this sounds like it would never happen, I’ve experienced this scenario myself. Several years ago, I worked on an application using LDAP. Previous applications within the company had been using a stable but not performant LDAP connection library. Another library utilized a better connection pool, which we wanted to try. If we had been held to being consistent with the patterns and tools in other applications, we would have never been able to attain the performance benefits of switching.

What to Focus on Instead

Instead of writing a consistent codebase that never veers from a known pattern, you should instead focus on the tried and true principles of building software:

- write simple code first

- optimize for readability and maintainability through code reviews and tests

- optimize performance via metrics and experiments

- iterative refactoring

It’s hard to go wrong with those principles.

Happy coding!

If you enjoyed this article, you should join my newsletter! Every other Tuesday, I send you tools, resources, and a new article to help you build great teams that build great software.

Dan Goslen is a software engineer, climber, and coffee drinker. He has spent 10 years writing software systems that range from monoliths to micro-services and everywhere in between. He's passionate about building great software teams that build great software. He currently works as a software engineer in Raleigh, NC where he lives with his wife and son.