My New Favorite Pattern for Writing Simple Code

March 03, 2024 | 5 minute reading time

Several years ago, I wrote an article called “My Top Four Patterns for Writing Simple Code.” Five years after writing that post, I still stand by those patterns. I use each of them almost every day.

I’ve recently been discovering a new pattern that I wanted to share as a follow-up/extension to that original post. I’ve found it especially effective in building and designing event-driven architectures. It isn’t a new pattern by any means, but I’ve been discovering a few ways to make it much more useful than it might seem at first.

Executors and Commands

The pattern I’ve been discovering is most commonly known as the Command Pattern. This pattern’s core idea is to turn actions into data and communicate those actions between components using a unified interface. This allows us to decouple an action/message from the sender and receiver, which makes it easy for components to communicate without knowing each other’s implementation details. Additionally, the thing being sent or executed is defined by an interface, allowing multiple implementations to define their version of that “thing.”

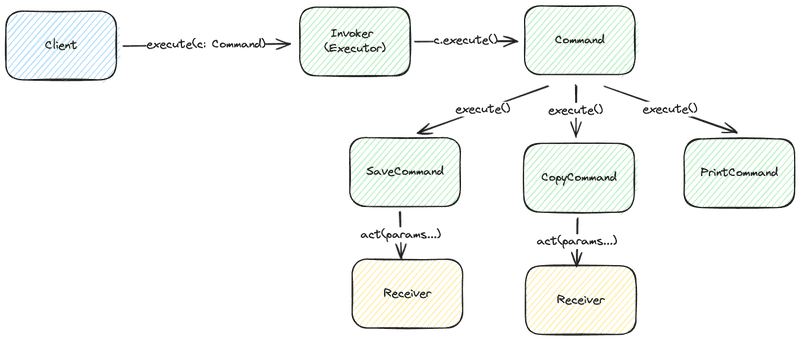

In the command Command Pattern language, we have three main components or objects:

Receiver: the concrete action to process or actor that needs to be called. It could be sending a request, modifying the state, etc. AReceiverneed not be a full-fledged class - it could be as simple as a function.Command: the interface that abstracts what needs to be done.Commandshold references to theReceiver.Invoker(akaExecutor): a class that is responsible for executing aCommand. I’ll refer to theInvokerfrom here on out as theExecutorfor the rest of this post.

Together, they work like this:

As we pointed out earlier, not all commands need a distinct Receiver object. Some Commands might be trivial enough that they simply store a small function instead of an object. In our diagram above, the PrintCommand might merely print the Command details to the console. It doesn’t need any additional Receiver or business logic object to do that. However, the SaveCommand or CopyCommand might need to know details about where (the Receiver) to save or copy to.

The Executor as an Interface

One of the best ways to extend this pattern is by making the Executor an interface as well. Making the Executor an interface means that we can easily add or compose behaviors at runtime without changing the structure of the code. This allows for more flexible code and easier testing.

A good example I’ve loved around the Command Pattern that perfectly illustrates the value of making the Executor an interface is ordering a meal at a restaurant. Many restaurants now allow for various types of ordering beyond being in person. You can order online, call your order in, through some other mediator (DoorDash, UberEats), etc.

You can conceptually think of your order as a Command. You specify what food and drinks you would like, but you don’t know very much about the kitchen staff preparing your order (the Receiver). You also don’t know much about who will deliver your meal if you ordered delivery, either (another Receiver).

What does change is the Executor. When ordering in person, you likely will interact with a waiter/waitress or a staff member at the counter. You could also call in, which might mean you talk to someone different than if you had walked in. When ordering online, you will interact with the online ordering system.

In each case the way your order (the Command) gets to the kitchen staff (the Receiver) likely changes in each flow. If you are dealing with a waiter, they might temporarily record your order on paper first, then enter it into a computer system quickly after. If talking to someone on the phone, they are likely entering your order into the computer system as you speak.

It’s also important to see in this example that you might have layers of Executors via a delegate pattern. The computer system might be the centralized Executor for adding an order to the kitchen staff’s queue, so the other Executors (waiter or phone operator) essentially wrap this Executor as a delegate. For online delivery services, their conceptual Executor will send your order to the restaurant while also dispatching a delivery driver.

The Execution Context

While the Command Pattern is great, a gap appears in how to wire up your Executor and Commands. While seemingly trivial in a class diagram, in a real-world application, you might want interchangeable Executors (because we made it an interface) along with your defined Command objects for testing and different use cases.

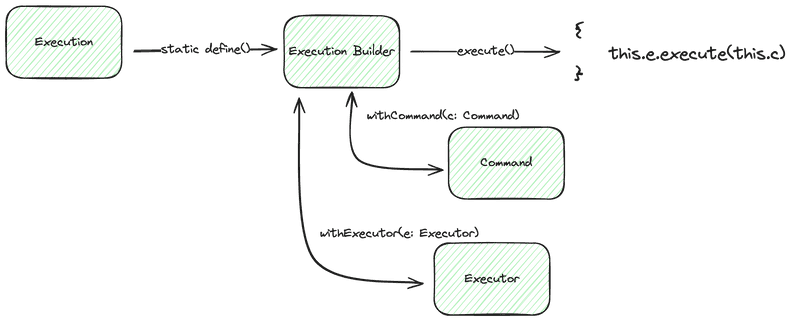

A way to bridge this gap is to create what I call an Execution Context or just Execution for short. An Execution is a specialized version of the builder pattern tailored for composing a Command and an Executor in a declarative way.

An Execution has a static method called define(), which returns an ExecutionBuilder. This component uses a fluent API to allow the client to call withCommand(c: Command) and withExecutor(e: Executor). The benefit of this approach is that we can change the Executor at runtime to any other Executor, but we use a constant “style” for doing so. As a component diagram, it looks like this:

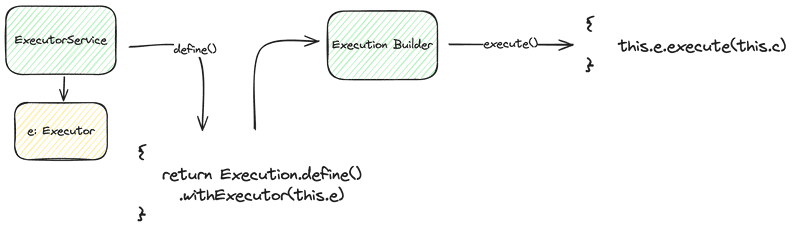

This is especially important for packages/libraries that want to expose a default behavior but want to allow for overrides. A library could define another higher-order component, such as an ExecutorService, which has a default executor configured upon instantiating that module.

To make it easy for an application to define a one-off use case with a different Executor, the ExecutorService could also have a non-static method called define(). This method internally creates an ExecutionBuilder, supplies the default Executor to it, and then returns the ExecutionBuilder to the client.

The result? The client can supply its Command to the builder and easily supply its own Executor as well. You can even use an extension to allow the ExecutionBuilder to have a fluent API for defining the Command itself, which makes for extremely declarative and easy-to-understand code.

Let’s see a (trivialized) example.

Usage and Example

As mentioned earlier, I’ve found this pattern helpful in event-driven architecture systems. For example, let’s say we have a Kafka message on the topic ORDER_PLACED. We want to place the order on the kitchen’s queue for them to fulfill

At it’s core, this is as basic as deserializing the message and placing it in the kitchen’s queue. However, there might be other needs. We might want to persist the order in another location for analytics. Or maybe we listen to multiple events in other areas of our system and want to make sure we track each of them consistently, starting or completing distributed tracing, etc. We don’t want our processing of an order to get complected with some of these other concerns.

One way would be to define a library with an Executor that is built to handle some of the common needs. If we follow the Execution pattern outlined above, we could define that Executor as a default value in an ExecutorService that we can then pass via dependency injection to our application. Our application can then use the .define() method to start a fluent declaration of what to do when processing an order.

An example might look something like this:

class OrderService {

// The ExecutorService is configured with a default Executor and is from an internal library

// The Custom Executor is defined by the application (here as an example)

// The KitchenReceiver is what we want to do with the order when we receive it

constructor(

private readonly executorService: ExecutorService,

private readonly customExecutor: Executor,

private readonly kitchenReceiver: KitchenReceiver) {}

@MessagePattern("ORDER_PLACED") // Tell our application to route messages from Kafka to this function

function placeOrder(message: object) {

this.executorService.define()

.withRawMessage(message)

.withExecutor(this.customExecutor)

.withReceiver((message: object) => {

const order = plainToInstance(Order, message);

this.kitchenReceiver.enqueue(order)

})

.execute();

}

}

Not much more to it :)

This pattern is extensible in many ways. A RetryExecutor could be created to retry failed executions; a registry could be designed to execute a Command via a token/name across the application, etc.

I hope you find this pattern as helpful as I have!

Happy coding!

If you enjoyed this article, you should join my newsletter! Every other Tuesday, I send you tools, resources, and a new article to help you build great teams that build great software.

Dan Goslen is a software engineer, climber, and coffee drinker. He has spent 10 years writing software systems that range from monoliths to micro-services and everywhere in between. He's passionate about building great software teams that build great software. He currently works as a software engineer in Raleigh, NC where he lives with his wife and son.