The Four Types of Code Reviews

January 31, 2023 | 8 minute reading time

Photo by Caleb Jones on Unsplash

Many engineers who have read my blog will know I talk a lot about code reviews. I firmly believe that a healthy code review practice is a critical tool for building a great team. It’s easier to build great software if people feel safe enough to ask questions, are generous in sharing their knowledge, and welcome feedback. Code reviews help build all of those things.

But many engineers assume that the only way to review code is via the pull request model. Pull requests are the default method for reviewing code - my writings on code reviews center around the pull request model, too, including my upcoming book! - but it isn’t the only way to review code.

In this article, I want to give a brief overview of four types of code reviews I’ve seen used by teams. The goal isn’t to show that one is better or worse than the other; the goal is to show that each is different. As an engineer, knowing when and how to utilize each of these methods properly will help your career. I know they’ve helped mine.

Review Dimensions

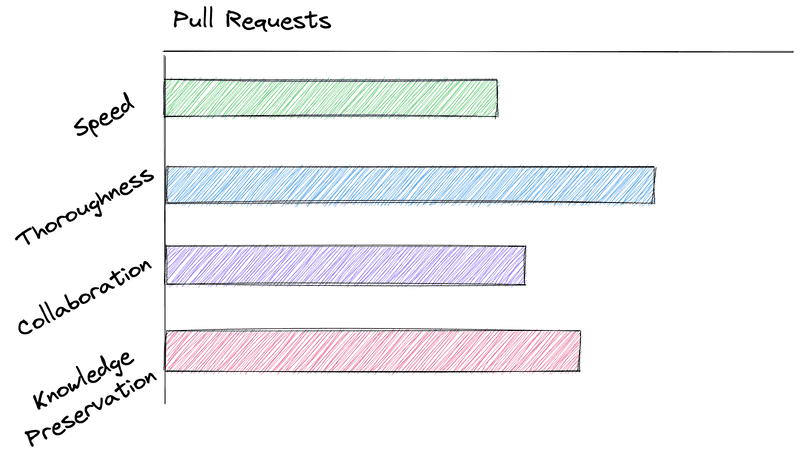

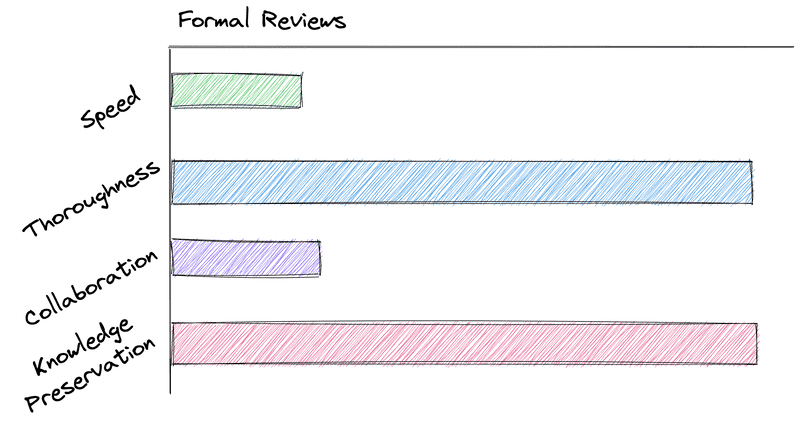

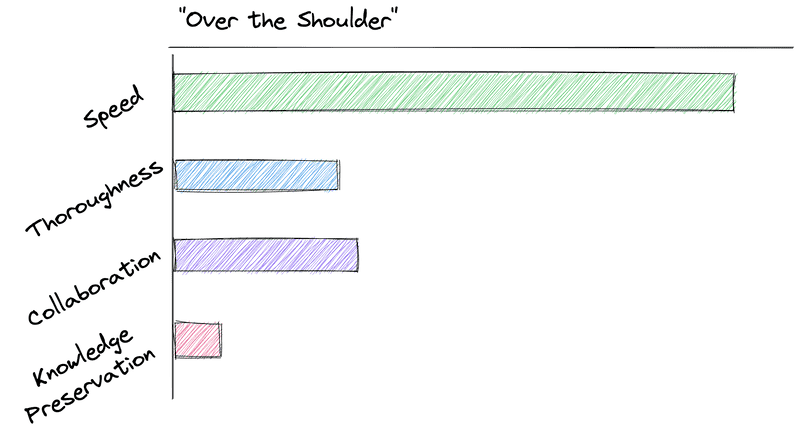

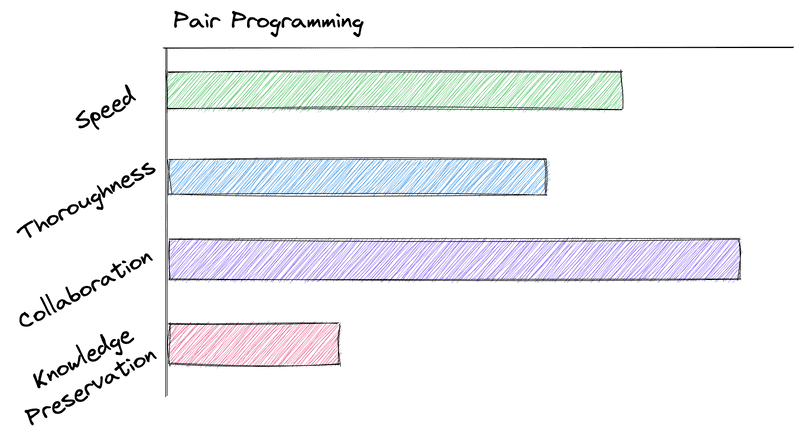

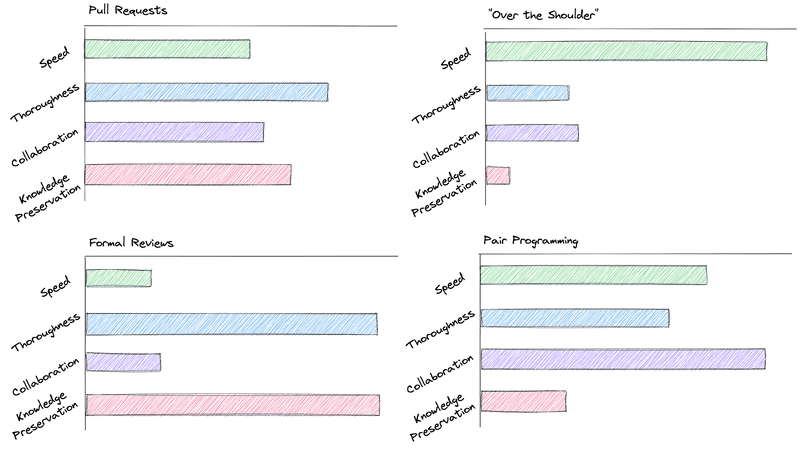

To help compare each of these code review methods, I’ve made some simple bar graphs to help illustrate how each performs on a few dimensions. Here is an overview of what I mean by each dimension I visualize.

Speed

Speed is the combination of both lead time and cycle time. Lead time is the time from when an author requests a code review to when they get the first review. Cycle time is the total time between when the review is first requested and when the code gets merged. The slower the code review method is, the longer it takes code to make it to production.

Thoroughness

Thoroughness is how complete or detailed a code review method is. Thoroughness is a direct correlation to the rigor of the method. A more detailed and prescriptive process is often more rigorous than one with fewer rules or directives. The higher the thoroughness, the more likely the review will find a defect or bug.

Collaboration

Collaboration is how well the method facilitates collaboration between the author and reviewer. It doesn’t take into account whether the method uses online tools or if it simply encourages people to talk together. Instead, it looks to see if the method makes it easy for engineers to give and receive feedback from each other.

Knowledge Preservation

This is how well the method documents decisions or outcomes from the code review. For example: if two engineers decide to go with a specific implementation over another, how easily can other engineers discover why that decision was made? Knowledge preservation is also essential for future engineers learning and understanding a new codebase.

Pull Requests

Pull requests are the standard in the industry. Originally brought to life by GitHub, this process allows a developer to batch a set of code changes (usually onto a branch) and request that the maintainer (or collaborator) pull or merge their code into the mainline branch.

Developers can discuss the code by leaving comments on specific lines of code or the code overall. Reviewers can also approve or reject the changes and require a certain number of approvals before being allowed to merge in the code.

Many tools also work well with the pull request model. Linters, automated tests, etc., can all run and report back on the pull request the status of each action - all with links and visual queues. Process checks (did the author remember to update the changelog or apply the proper tags) are helpful here too.

Pull requests grew in popularity as it was beneficial for open-source projects as they facilitated low-trust code from forked repositories. Prospective contributors fork the repo, make changes in their repo, and ask maintainers to pull their code into the original repository.

In some ways, a pull request is akin to a formal review, as every line of code can be reviewed by the reviewer. It depends largely on the reviewer’s thoroughness, however, as the process isn’t strict about enforcing every line is reviewed. It, therefore, rates pretty high on thoroughness but below a formal review.

Pull requests are generally quick (though that is a hot debate) as long as the request size isn’t too large. The larger the request - measured usually as total lines changed - the longer it takes to go through review.

Pull requests also score decently on collaboration. Much of this collaboration is facilitated by the tools developed by GitHub (or other git SaaS providers) to easily suggest a line change or comment on the changes overall. Many engineers, however, don’t love the pull request process, citing that the asynchronous nature of a pull request introduces additional lag in the system (which is correct). In my experience, however, this waiting time is only pronounced when the team isn’t working together already.

One of the best parts of using pull requests is that conversations are visible to the team, and they even last after the review is over. This has a massive benefit overall as the team can (and often will) utilize the pull request to view what change occurred and discover learnings or discussions around that change too. It isn’t a perfect record, but it sure does help.

Formal Reviews

Formal reviews are the most demanding form of code reviewing. In formal reviews, a team of engineers goes through the code line-by-line, looking for defects or gotchas. Sometimes teams utilize printed copies of code, though this practice is less common in our environmentally conscious world.

A common approach to formal reviews is called the Fagan inspection - a process named after software engineer Micheal E. Fagan. Fagan was a researcher for IBM and was a pioneer of software inspection. His technique is methodic and prescriptive for each stage of the review and how it should be conducted, including steps before and after every meeting where the review actually takes place. Not all formal reviews are as prescriptive as Fagan’s, but they do often have more overhead than “just reviewing the code.”

This overhead leads to formal reviews taking longer and being much less collaborative than other review formats. We’ve all experienced how hard it can be to schedule a meeting with four or five attendees leading to an increased waiting time. Additionally, once feedback is given, an engineer might be sent to work alone to implement the required changes. They then have yet another meeting to schedule for a second round of review. It feels like useless bureaucracy in the modern Agile software world…

Where formal reviews do excel is in their thoroughness and knowledge preservation. The process of methodically going line-by-line through the code can often lead to a deep understanding of the code base and the discovery of new edge cases originally not thought of. The formal review process will make sure to document each of these findings - not just for the coder to implement but for the product owner, testers, and other stakeholders to be aware of too.

Formal reviews are now often reserved for the most critical and safety-conscious codebases. Self-driving cars, medical devices, etc., are all candidates for such a review.

“Over the Shoulder”

Over the should is precisely what it sounds like: an engineer invites a colleague to peer over their shoulder to double-check their work or look at a specific problem with them.

While this method might not feel like a code review, it certainly is. One engineer asks another engineer to review their code for either help, direction, or even a quick affirming approval.

Over-the-shoulder reviews are rapid and often very low effort. This makes them ideal for small, close-knit teams working together on the same product or project.

However, this speed also comes at the cost that details are often missed since the reviewing engineer usually has little more than a “Hey, can you take a look at this with me real quick?” Depending on the context, this likely isn’t anything to be concerned about. Most teams will use an additional review method before merging code anyway.

Interestingly enough, because over-the-shoulder reviews often focus on a specific need or problem, they don’t encourage much collaboration. They might, however, lead to setting up a pair programming session, which (as we will see next) is highly collaborative.

Where over-the-shoulder reviews suffer is in the area of knowledge preservation. If a pair of engineers discovered a new bit of knowledge while working together, there is no natural place to store that knowledge (at least no place immediately close to code). Even if there was, it might be challenging to make that knowledge discoverable for other team members as the context - the change they were working on - can be easily lost.

Pair Programming

Pair programming is similar to the over-the-shoulder review but requires more prescription and rigor. In pair programming, two engineers work together on a specific piece of code with assigned roles and responsibilities for working together. They are often co-located, sharing a single computer but each with their own mouse and keyboard.

These roles are often called the Driver and the Navigator. The Driver is responsible for writing the code, while the Navigator looks for minor mistakes and thinks strategically about the direction the code takes. Often the pair of engineers take turns rotating through each role.

One of the key ideas of pair programming is that by reviewing code at the time of writing, there is a higher chance of catching defects early. Catching defects early should mean the team is building quality into the code from the start rather than trying to inspect the code after the fact. It stems from the idea that reviewing code after it is written is simply too late. The famous quote from W. Edwards Demming helps to really solidify this perspective.

Inspection is too late. The quality, good or bad, is already in the product.

Pair programming is about working together in real-time to collaboratively discover and refine high-quality code before it is ever committed to the codebase. As Dragan Stepanović says, “the optimal time to review any line of code is immediately after it is written.”

Pair programming also tends to go hand-in-hand with Extreme Programming or XP. In XP, teams utilize continuous integration, trunk-based development, and other methods to optimize shipping code to production as fast and safely as possible. Pair programming works well in XP as two engineers can work together on a small piece of work, decide it’s ready, and commit it to the main once they are done - relying on their automated test suite to fail the build before pushing to production.

As mentioned earlier, pair programming can be seen as a formalized over-the-shoulder review. It, therefore, ranks high on speed since there is a fast feedback loop. It does better than over-the-shoulder reviews on collaboration though it goes beyond a quick check of a single line toward a complete solution written by both participants.

It also has many of the same drawbacks. Pair programming tends not to be as thorough as formal reviews or pull requests. Yes, the code is getting reviewed immediately, and both engineers are looking for bugs. But, since the conversation is often happening in real-time, and fatigue is real, I’ve seen many pairing sessions get focused on getting something done such that an edge case gets overlooked or a corner gets cut. This isn’t necessarily wrong, but having a time buffer can allow deeper thought about the code and its implications on the product and could base that a real-time feedback loop might not permit.

Pairing also doesn’t solve the problem of knowledge preservation either. Two engineers (or potentially more if utilizing [mob programming]) could decide on code to refactor something but never publish to the rest of the team why that decision was made. If another team member is trying to understand the change, they will likely have to get one of those engineers to explain why.

Use Each Method When Called For

Phew! That was a lot! Thanks for hanging in there.

All of this is to say that each of these methods has different strengths and weaknesses. It’s up to you and your team to wield each as necessary as you build software. Your team might gravitate towards pull requests (which is common) and use pairing on complex work or to expedite a particular piece of work. A formal review might only be used on something new and where the whole team needs a deep understanding of what the code is doing.

But they are all valuable in their own right.

Happy coding! (and reviewing!)

Here is a side-by-side comparison of how each of these methods rank in terms of speed, thoroughness, collaboration, and knowledge preservation:

👋🏼 p.s. If you liked this post, you'll love my book, Code Review Champion! In it, I share everything I've learned from over a decade in the industry about building a code review practice to set you and your team apart!

If you enjoyed this article, you should join my newsletter! Every other Tuesday, I send you tools, resources, and a new article to help you build great teams that build great software.

Dan Goslen is a software engineer, climber, and coffee drinker. He has spent 10 years writing software systems that range from monoliths to micro-services and everywhere in between. He's passionate about building great software teams that build great software. He currently works as a software engineer in Raleigh, NC where he lives with his wife and son.