What's the Point of Blameless Postmortems?

May 08, 2023 | 6 minute reading time

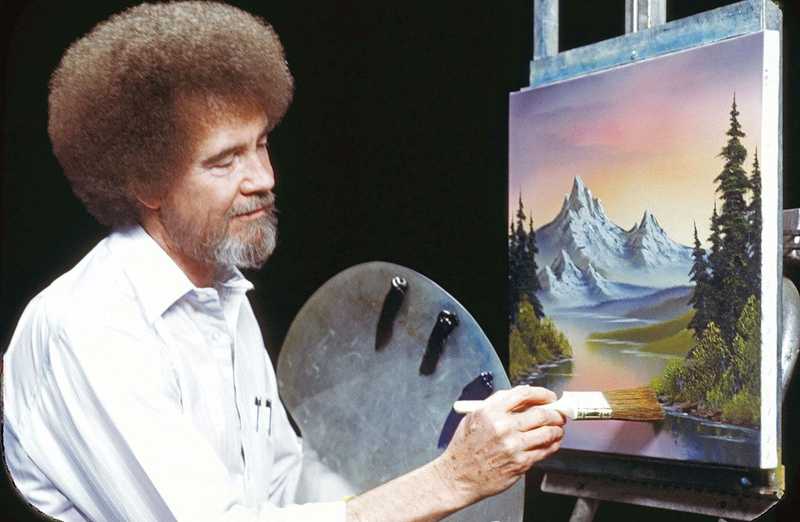

Do you remember Bob Ross?

Bob Ross was (and still is) an icon to many Americans. He hosted a program on PBS called The Joy of Painting in which he would paint a new painting every episode, usually of a serene landscape.

Ross was known (at least on TV) for being soft-spoken and had a mentality to his painting that has lived on as his legacy. To him, you didn’t make mistakes; you made “happy little accidents.”

Our team at Policygenius has tried to adopt this phrase in our engineering culture around incidents and outages. We want to see everything as an accident - no one did anything intentionally, and no single person is to blame.

This idea is often referred to within the software industry as having a blameless culture. Instead of searching for some individual or team to blame for an outage, the idea is that the outage is likely due to a series of failures rather than one responsible party.

This characteristic often comes up during the writing and review of a postmortem document. How your team goes about reviewing an incident and the next steps after says a lot about how your team accomplishes work.

Let’s dive into how to build a team that hosts blameless postmortems and how it helps them succeed.

What Exactly is Postmortem?

A postmortem in software is the examination of an incident to understand the underlying cause of the incident. The hope is that by identifying an incident’s cause(s) after one occurs, we can learn something to help us avoid the next.

A typical postmortem will discuss a few critical pieces of information. The formats across different organizations will look different (and you can see a great collection of examples on GitHub, but they all will roughly cover these six sections outlined below.

The impact of the incident: who was affected? How long did the incident continue? Did we lose money or customers? The timeline of the incident: how were we alerted to an incident? Who was on call? Who responded? What actions were taken and when? The root cause(s): did a system fail? Was the request latency too long? Did a vendor fail or a database crash? The resolutions: what actions were taken to mitigate or resolve the incident? Is the incident fully resolved, ongoing, or only partially mitigated? The action items after: what steps will teams take to avoid incidents like this in the future? Does the code need to change? Alerting procedures? Deployments?

Postmortem docs are often also usually written by the primary incident on-call team and then reviewed by the entire engineering org. Large organizations (think 100+ engineers) might restrict the review to only closely related teams. Keep in mind, though, that the broader the audience, the more opportunities there are for learning.

This article won’t cover the inner workings of writing a great postmortem document as there are plenty of articles for that from Atlassian, real-life examples from GitHub and many other resources.

Instead, I want to focus on the importance of making them blameless and the cultural shift that has to occur for it to be possible.

Who Do We Blame?

As hinted at so far, one issue with a postmortem document is that once the smoke has cleared and everyone sees what happened, it can be tempting to find a person or a team as the culprit.

Depending on the severity of the incident (a multi-hour outage, for example), leaders might be looking for scapegoats to send a message of authority. Other teams might want to pass the proverbial buck from their failures to a different team claiming their systems failed first.

Everyone wants to pass the blame and point the finger.

But once this begins to happen at an organization, something terrible starts to happen: people start to lie. They start covering things up or biting their tongues on issues they see. And this can lead to disaster.

Teams will cover up details of the incident to hide their involvement. Incident responders with ideas on how to correct the issue might not mention it to the group - they might attempt to fix it in secret, hoping no one notices.

Worse, over time, this culture of fear begins to permeate every aspect of development, leading engineers to avoid bringing up issues in code reviews or bringing exciting ideas to their products. You will lose engineers and ideas and slowly fall behind.

Most importantly, a blaming culture actually leads to more incidents over time. None of the underlying issues get addressed or fixed. Bugs that caused multi-hour outages lurk in code months or years into the future. Ticking time bombs for the next thing to go wrong.

How do You Make a Postmortem Blameless?

So how do you start to make your postmortems blameless? You need more than a nice document that avoids throwing people under the bus. You need a culture shift.

Culture shifts happen in various ways. In software, many efforts start bottom-up. Such efforts include improving observability or refactoring an old system. No one asks for permission in a bottom-up culture shift, they just start to act in ways they believe are better, and others begin to follow.

A culture of blamelessness or safety very much happens top-down. At some point, a leader (or group of leaders) needs to begin creating patterns and practices to enable a blameless culture. If a team is blameless in their daily work on their own, that is great! But directors and above believe that people shouldn’t be fired for a botched deployment, things will stay the same.

That doesn’t give you a hall pass as an engineer, though. You have a role to play in shifting the culture. After all, the culture is a collection of values, beliefs, and behaviors shared across the company.

The best way to aid this sort of change includes both modeling the behaviors you want to see and advocating for them to your leaders.

Model it by taking ownership of your part in any incident involving your team. Model it by avoiding pointing fingers and focusing more on what happened than who caused it. Lead by working to identify a set of next steps to avoid the issue in the future and volunteering to work on one immediately. If you write are the one writing the postmortem, make sure to embrace Google SRE’s perspective:

Writing a postmortem is not punishment—it is a learning opportunity for the entire company

Concurrently, you should advocate for these changes to your manager and other leaders. Build a case citing research from Accelerate, the DevOps handbook (discussed in the section below), and the overall benefits of psychological safety that builds effective teams. Find like-minded peers to help push the shift forward rather than going solo.

You might not fully convince them, and that’s ok. Shifts like this often take time and many rounds of effort to happen. Just don’t sit idle and watch it all happen.

Does it Work?

But what if all of these changes don’t affect anything? Will a blameless postmortem help to prevent outages in the future?

Thankfully, we have a lot of data that says emphatically: yes.

Research from Google, Gene Kim via the DevOps Handbook (which includes companies like Etsy and HubSpot) all agree that postmortems are critical to their success. Blameless postmortems are anchors to a culture of physiological safety where mistakes (or happy little accidents) show a fault in the system rather than a fault in the people.

I can also speak directly to the effectiveness of a blameless process in my career. On teams in which incidents or outages were meant by immediate blaming, shaming, and even firing related parties, the result was simply that no one wanted to ship software. People were so afraid to make a mistake that they would waste hours (literally!) trying to avoid shipping a feature. This led to larger and larger releases further and further apart: a recipe for more failed deployments and incidents.

These teams also tried to keep a low profile on what went wrong in their incident. Then the next week, a different team would make the same mistake because they couldn’t learn from the previous mistake.

On the flip side, by learning to focus on what happened and what we can do next time to avoid it, teams focus on solutions and action. Teams take ownership of their failures (absent from pressure or pointing fingers) and also own the action steps to avoid them in the future. Everyone learns from each other’s successes and failures rather than insights remaining siloed within team boundaries.

Accidents Happen

The takeaway from this, I hope you see, is that accidents happen. Instead of focusing on removing those who make accidents, we need to build a culture that doesn’t default to anger or punishment for an accident.

There are times, of course, when someone does need to be let go after repeated carelessness or downright lack of concern. But more often than not, someone simply logged into the wrong terminal and thought they were in a different environment.

Let’s work on learning from accidents to prevent the next one rather than scolding for failures that have already happened. A culture in which we reward those who do the right thing more than punishing those who make a mistake.

And our teams will grow as a result. And that is what it’s all about.

Happy coding!

If you enjoyed this article, you should join my newsletter! Every other Tuesday, I send you tools, resources, and a new article to help you build great teams that build great software.

Dan Goslen is a software engineer, climber, and coffee drinker. He has spent 10 years writing software systems that range from monoliths to micro-services and everywhere in between. He's passionate about building great software teams that build great software. He currently works as a software engineer in Raleigh, NC where he lives with his wife and son.