Tuckman, Teams, and Bruce Lee

April 23, 2023

Working as a software engineer in today’s world often requires working with others. The top tech companies, fintechs, and even up-and-coming disruptors organize their engineers into teams with specific missions, goals, and ownership. It might be the fabled two-pizza team, or it might be a team of ten or more.

Learning to work well within a team is critical to your success as an engineer. The notion of the hero programmer or the lone ranger won’t get you far. The top engineers are ones that accomplish through others by mentoring, teaching, and shaping the organizational culture. And it’s hard to do any of those things if no one wants to work with you.

But the thing about teams is that they change. New members join, old members leave, reorgs create brand-new ones, etc. And when this happens, it can be hard to understand what to do next.

But it’s paramount that when these changes happen that you do adapt. Otherwise, you will get stuck in the past.

This begs the question: how do you adapt? How do teams change?

Much research has gone into how teams form, perform, and find their roles on their team (which we’ll get into it soon). But before we get there, whenever I think about adapting, I think about Bruce Lee.

Be Like Water

I’m not a big kung-fu movie buff. But I’ve still heard of Bruce Lee.

Bruce Lee was one of the world’s best martial arts movie stars. Not only did he master the craft of martial arts, but he was a master filmmaker and even a bit of a philosopher.

And there is one quote of his that exemplifies how to adapt on a team.

Be like water making its way through cracks. Do not be assertive, but adjust to the object, and you shall find a way around or through it.

What does this mean in the context of navigating team changes?

It means to be flexible. Don’t try to push your agenda over others or force your will on the team. Instead, find the paths or the directions of the team you can follow to create momentum for your team and its goals.

An example of this from my experience on a team change was around alerting. When I joined a new team several years ago, they had a very intense alerting process, and I wasn’t used to such a rigorous process for the on-call engineer. Quite frankly, I found it annoying.

Over time, I realized how beneficial those alerts had been in keeping our team’s SLA intact. But, after a while, I realized that only a handful indicated a real issue, and I worked with the team to limit the number of alerts to only the most critical ones.

We improved the process for on-call engineers, giving them more time to work on other improvements than constantly checking alerts that wound up not being a big deal.

If I had stood up on day one of joining that new team and proclaimed, “We have too many alerts,” I would have been told, “But these alerts are critical to upholding our SLA. We can’t change them.” But by joining the team, being flexible, and adapting to the team’s processes, my suggestion to reduce the total alerts was welcomed. I was now a member of the team rather than being perceived as an outsider.

This prompts another interesting viewpoint: what does it mean to be a team member rather than just being a new person on a team? What does being a team even mean?

It’s a great question full of research from many angles, but today I want to focus on just one model: the Tuckman model.

The Tuckman Model

The Tuckman Model is a general model used to describe how groups move from becoming a set of individuals to being part of the group. How someone shifts their participation from “the team I work on” to “my team.”

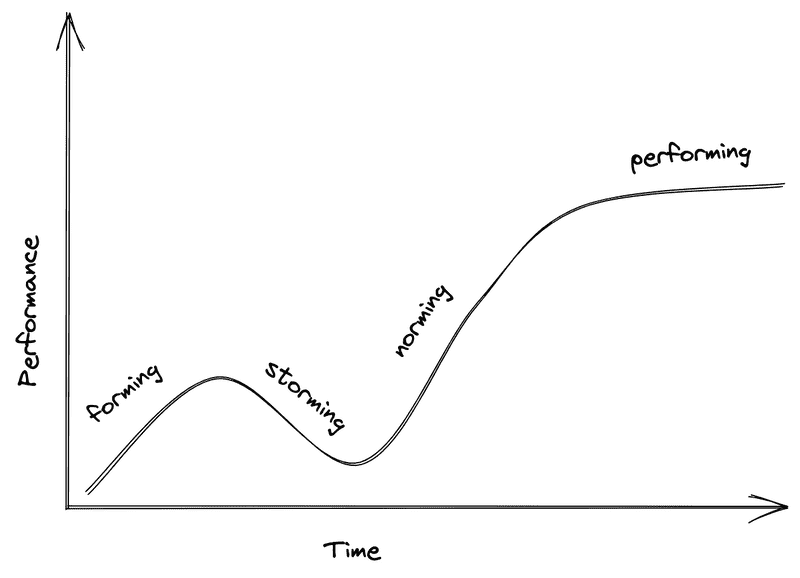

In this model, the team goes through four stages: forming, storming, norming, and performing.

Forming

In this stage, the team is trying to understand two core questions:

- what is this team, and what does it do?

- what part do I play in it?

Team members are often motivated, polite, and willing to give their best. But they are still trying to figure out the team’s practices and goals, and are searching for boundaries of what is acceptable.

It’s crucial in this stage to ask questions that help clarify the team’s goal. The team must work together to agree on their goals and things like vocabulary, regular meetings, and expectations.

If you are a leader or more experienced engineer, this is a great time to go first. Junior engineers will be looking to you to set the tone and culture of the team. Don’t be aggressive in asserting your agenda (remember - be like water). Still, you can go in first by asking questions, suggesting ideas, and publicly supporting ideas from others you think will be helpful.

Storming

The storming phase is exactly what it sounds like. In this phase, the team grows charged with tension, disagreements, and conflict. Some teammates will have grown frustrated with each other’s behaviors and finally feel safe enough (or simply too exasperated) that they express their frustration. Performance starts to drop as the team is now more concerned with how they achieve their goal rather than what that actually goal is.

Most engineers would want to skip this phase. And why wouldn’t you? Being on a team with tension or conflict is never fun.

However, you aren’t powerless during this stage. Don’t ignore the tensions or conflict. I’ve been on times that tried to pretend it didn’t exist, and it only grows worse.

While there is no perfect way to handle any disagreement or conflict, one thing I’d advocate for is turning to your manager or team leader. Describe what you see and things you would like to change. If you are struggling to work with someone specifically, ask for guidance on how to discuss it directly with that person from your manager - but avoid gossiping or creating tribes within the team.

Remind each other (and yourself) that everyone is trying their best. Work to overlook minor differences in style and instead look for what you can learn from each member on your team. You want to create trust between the team, which must be both earned and given.

If you are willing to tackle the storming phase head-on, you will minimize the duration and intensity of this phase, allowing you to move to the third stage stronger than ever.

Norming

Norming is the tail end of storming and continues as the group begins to tolerate each other’s differences while also establishing the patterns and culture of the team.

In this stage, team members also learn a deeper sense of what they can contribute. As this happens, each team member must have opportunities to make contributions that they find meaningful. If you are a leader or experienced engineer, look for ways to empower your team members to do just that.

This stage can continue for a long time, and that’s ok. This process is vital for cementing long-term culture and behaviors that will carry the team into long-term success.

Use tools like retrospectives and blameless post-mortems so the team can see where they have room for improvement and define action items to do so.

Performing

After the period of norming is the performing stage. This is when things are going great for everyone on the team, and the team is achieving their goals.

It is also common for short “re-norming” spurts to occur in this phase. This might happen after an outage when process changes need to be made. Or perhaps the team has gotten a little too lax in their efforts and needs to put more in.

Whatever the case, it is essential to remember that small re-norming (or tuning stages) are critical to the team continuing to perform. The best sports teams in the world don’t coast on the success from last season; they constantly ask how to get better.

Swarming

In software, there is another common stage that is apart from the typical model: swarming.

You’ve likely heard of swarming as an activity for a team to do when something has gone wrong, or there is a high-priority problem to solve. Everyone on the team contributes ideas, code, research, etc., in order to solve the problem as quickly as possible.

A benefit of swarming is it acts as an immediate goal for the team to accomplish. If the team can effectively swarm and solve a problem, it will act as a quick win for the team, showing them that they can indeed succeed.

Swarming is a formative stage in the middle/end of the storming stage. With careful leadership and direction, it will help the team realize that some of their misgivings about each other are unfounded and that they can work better together than expected.

The last bit of wisdom I’ll leave you with is a quote (and I can’t remember for the life of me where I heard it but it seems to come from this Tweet):

Teams are immutable. Every time someone leaves or joins, you have a new team, not a changed team.

This is important because it means that not only will the Tuckman Model apply to a brand new team, but any change in personnel. This includes someone joining your team or you joining another. In all cases, a new team is formed.

You are likely to go through several teams in your career. Whenever you do, you have to remember you are actually creating a new team. No matter what the situation, you’ll have to be like water and adapt.

This will mean learning humility in some cases. In others, it might mean learning to ask questions. Or it might mean practicing empathy or starting to mentor others.

It will also serve you well to remember the Tuckman Model as you navigate your new team. Use it to anticipate conflicts and how the team will perform. Know that there will be times to lean in - to “embrace the suck” - and times to consider asking for help.

But if you be like water, you will form a truly incredible team.

Happy coding!

If you enjoyed this article, you should join my newsletter! Every other Tuesday, I send you tools, resources, and a new article to help you build great teams that build great software.

Dan Goslen is a software engineer, climber, and coffee drinker. He has spent 10 years writing software systems that range from monoliths to micro-services and everywhere in between. He's passionate about building great software teams that build great software. He currently works as a software engineer in Raleigh, NC where he lives with his wife and son.